Introduction to Cold Process Soap

If you are reading this blog post, chances are you have already heard of or have used cold process soap. It surpasses melt and pour as my favorite method of soapmaking for a number of reasons. So, what exactly is it and why is it known as “cold process” soap? Simply put:

Oils + Lye = Soap & Glycerin

The alkali (sodium hydroxide) and the fatty molecules (oils) combine to make a soap molecule. The glycerol separates, becoming glycerin (the moisturizing part of soap) and the water evaporates over time, which is known as the curing time. I always think of cold process soap as being “old fashioned” and believe it or not, there is actually nothing “cold” about the process. The alternative method, hot process soap, follows the same guidelines except the recipe continues to fully cook (cure) the soap in a heated crock pot.

My favorite thing about making cold process soap is that I get to control each and every ingredient that goes into the bar. I chose the oils in this recipe because they are affordable and have some wonderful skin-loving properties. Rice Bran oil is especially gentle for sensitive skin, which makes this a lovely soap for just about anyone. This recipe produces a nice, creamy lather with plenty of bubbles, thanks to the Coconut oil. A variety of oils are typically used because all oils have different types of fatty acids which contribute different properties to the final bar of soap such as lather, cleansing and moisturizing qualities.

This is where a soap calculator comes in handy. Since each oil is comprised of different fatty acids, they each react with the sodium hydroxide differently. The soap calculator takes these different factors into account and provides the proper ratio of water and lye to complete the chemical reaction necessary. I rely on SoapCalc.net but there are several great calculators online. Make sure you follow their instructions as each one works a little differently.

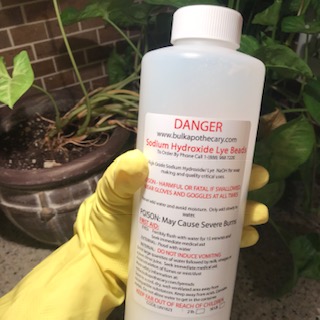

Before going any further, please refer back to our post on lye safety. It is EXTREMELY important you understand how to handle sodium hydroxide with caution. Mishandling of lye leads to injuries such as chemical burns and we do not want that! This is why it is fundamentally important to wear personal protective equipment (often referred to as PPE) such as long pants, long sleeves, gloves and protective eyewear.

It’s completely normal to be nervous the first time you work with lye, but try not to let it terrify you. Keep in mind there are already many household products we use on a daily basis that are dangerous if not handled properly. Take the necessary precautions and you’re good to go.

Here’s What You’ll Need:

9.6 oz. Sweet Almond Oil

8.00 oz. Rice Bran Oil

14 oz. Coconut Oil 76 Degree

12.16 oz. Distilled Water

4.79 oz. Sodium Hydroxide (Lye)

1 oz. Lavender 40/42 Essential Oil

Additional Supplies:

Heat Safe Containers

Cutting Board

90% Rubbing Alcohol

Digital Scale

Thermometer

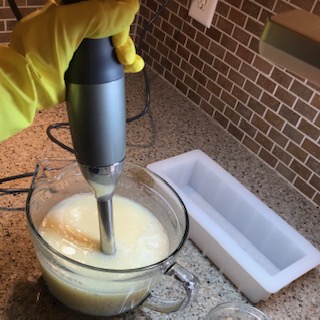

Stick/Immersion Blender

Gloves

Eye Protection

Long sleeves

A child and pet-free work space

Let’s Get Started

The first step you need to take is to clear yourself a work area with a generous amount of space. This type of soapmaking requires a lot of moving around, pouring of containers and use of different tools, so you don’t want any extra clutter around.

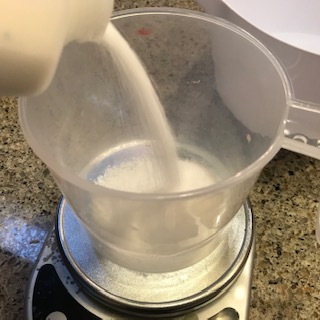

You will need a digital kitchen scale to weigh your ingredients properly. Remember, when we are working with soap, we are measuring in weight, not volume or fluid ounces – even with a recipe, failure to accurately measure ingredients will negatively effect your end result. I like to view cold process soapmaking as basically just chemistry made fun. Ensuring a complete chemical reaction when mixing oils and lye will secure you a successful batch of cold process soap.

At this point, I like to begin by weighing my water and fragrance. I have found that weighing everything in the beginning (except the lye, which you definitely do not want sitting out in an open container) helps me keep a good pace and doesn’t distract me by having to interrupt my flow to measure more ingredients. With that said, measure 1 oz. of Lavender essential oil and 12.16 oz. of distilled water in separate containers and set aside.

In another container, measure your liquid oils. It is best to weigh each oil individually and then combine, as this will avoid any over-pouring. If you choose to add all of your oils to one container, do not forget to tare your scale in between ingredients. I prefer to measure my solid oils/butters separately as I find it helps with accuracy and minimizing mess.

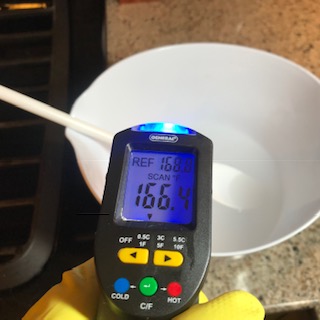

Once the oils are combined, it’s time to put them on the double boiler on medium-low heat. Wait until all oils are completely melted and transparent. Once the oils are completely melted or have reached 130 degrees, remove from heat and set aside to cool.

Measuring the Lye

Safety first! If you aren’t already wearing your personal protective equipment, now is the time to suit up. DO NOT PROCEED WITHOUT SAFETY GEAR!

Carefully open the 2 lb. container and gently measure 4.79 oz. of lye by sprinkling it into a heat-resistant plastic or glass container. Take care not to pour the lye from too high above – you don’t want to get it anywhere except the container. Recap the lye and store in a cool, dry environment. If left in unfit conditions, it will attract moisture from humidity in the air and begin to cake and clump.

There’s a common misconception that soap contains lye. This is not true. While lye is used to make soap, once a complete chemical reaction has occurred – known as saponification – there is no remaining lye in the bar of soap. This is why it is so important to accurately measure your ingredients. Overuse of lye will produce a bar of soap that zaps and is irritating to the skin. Using too little will result in a soft, squishy bar that contains too much oil.

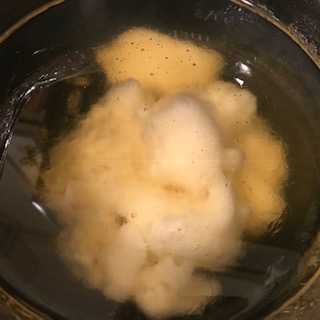

Measure 12.16 oz. of distilled water in a separate container. ALWAYS ADD LYE TO THE WATER! Do not add the water to lye. Doing so can cause splatter, lye caking at the bottom of your container and overheating. Slowly incorporate lye into the water by again gently sprinkling it in while slowly stirring the water. Continue to gently stir until all the lye has dissolved. As you can see, the lye water heads up relatively quick, reaching temperatures of up to 200° F in some cases.

There will be fumes at first! For this reason, It is important to mix the lye in a well-ventilated area.

Combining Oils and Lye Water

Allow the lye water and oils to reach 110° F or below. Temperature plays a key role in cold process soapmaking so you’ll want your lye water and oils to be within 10° of each other. If you soap at too high of a temperature, your soap will be prone to overheating which can cause the soap to crack down the middle and expand out of the mold.

Carefully pour the lye water down the shaft of the stick blender. Doing this will prevent any caustic water from splashing out. Once the lye water is completely poured, gently pulse the blender a few times until you begin to see trace.

So, exactly what is trace? Trace is what occurs when raw soap begins to thicken. There are 4 stages to watch for:

- The first stage is emulsification – this is when all evidence of oils are gone, but the mixture is thin and liquid-like. The lye water and oils are just beginning to combine.

- The second stage is thin trace – the mixture is opaque and when you lift your mixing tool out and let a drip fall back in, it will rest on top before sinking back in. This is when I typically add my fragrance or essential oil.

- Medium trace – you can lift a spatula out and drips will rest on top without mixing back in, you can “trace” trails into the top of the mixture and they will stay. The mixture will still be pourable and this is a good time to get it into the mold as it will be less likely to have air bubbles.

- Thick trace – a custard-like consistency. You will feel resistance when trying to stir. At this point you are better off trying to scoop your soap into the mold than pour it.

For this recipe, I will be mixing in the Lavender essential oil at thin trace. I pre-measured 1 oz. of essential oil so I didn’t have to interrupt my work flow to do a new measurement. This Lavender 40/42 essential oil is standardized to ensure consistency from batch to batch and it is perfect for soapmaking and other bath & body products. If you want to get fancy, you can even sprinkle some lavender buds on top of the soap when finished. I recommend using the Super variety of Lavender buds which are known for their vibrant purple color.

By the time the soap is in the mold, it will have thickened up a bit more. I use this block of time to give the top of my soap some texture. I used a wooden skewer to make swirls for this batch. You can smooth it out with a spatula, add texture with a fork, spoon, almost any utensil you’ve got will work. This step is completely optional but it’s fun to jazz it up a bit. When you are finished texturizing, give the soap a few sprays of rubbing alcohol. This helps prevent soda ash which can be unsightly. Soda ash occurs when unsaponified lye is exposed to carbon dioxide in the air and is purely cosmetic.

Store the soap in a safe place that is out of reach of children and pets. Now the waiting game begins.

Unmolding the Soap

It is important to allow the soap to set in the mold for at least three days. Since this recipe is composed of liquid and soft oils, it takes a little while longer to solidify.

I highly recommend placing the soap loaf in the freezer a few hours prior to unmolding. Since the soap is still soft at this point, the freezer helps make unmolding a breeze. Pull away at each side of the mold, flip over and push down on the bottom and wait for the vacuum seal to release.

Cutting the soap while it’s still cold is a good idea. Having it in a more rigid state will allow for easier slicing. You can use a soap cutter or a kitchen knife. This recipe yields approximately 10 x 1″ bars of soap.

Allow the soap to cure for at least 4 to 6 weeks. Remember how we mixed lye into over 12 oz. of water? Well, that water is still in the loaf of soap and needs to evaporate. This is exactly what happens during the curing process. The excess moisture is able to leave the bar when exposed to air, which results in a harder, longer-lasting bar of soap.

In Conclusion

Cold process soapmaking is such a valuable skill to have. It gives me a sense of self-sufficiency and self worth. I too was hesitant at first, but I didn’t know I could do it until I did it! Now I’m constantly brainstorming for new ideas and new recipes. I’ve got a lifetime supply of soapy gifts for my family and friends!

Soapmaking allows you to craft something practical that is definitely not going out of style any time soon. There will always be a need for soap! You can even formulate recipes for laundry soap or shampoo bars with this method. You can tend to your hygiene with the peace of mind because you know exactly what is in that bar of soap. Cold process has so many different techniques to learn and we look forward to sharing these with you in the coming months.

Have you started cold process soapmaking yet? If you are an experienced soapmaker, what piece of advice would you offer to a beginner? Let us know in the comments below!

I think the ‘cold’ from ‘cold process’ comes from the fact that you aren’t curing the soap in heat.

you might wish to change the word “detrimental” to another. someone else posted this suggestion to your Facebook post

can I substituted rice brand oil?

Yes!

for what? could i use the same amount of sweet almond oil? or what oil could i use

Is it a hard bar?? Should we need a harder like sodium.lactate?

If sodium hydroxide has gone hard, completely solid, in the container, can it be somehow broken apart in order to use it for soap making, or is it no longer able to be used once it has become solid (and no longer in flake form?)? Thank you for your help!

Hi, is it safe to assume you’re converting ounces to grams when weighing out your ingredients?

Thank You

Hi, there! We are actually an American company so we do keep our weights in ounces. However, you are welcome to do the conversions to align with your scale. Thanks!